The RBA's David Jacobs and Susan Black published an article in the November 2006 RBA Bulletin that provides a good assessment of the current status of the Australian hedge fund industry. This article follows comments by the Governor (see Reserve Bank of Australia's Stevens Flags Australian Hedge Funds Risk). The article was picked up in a story by Fiona Buffini of the Australian Financial Review on 17 November 2006 in which she highlighted the surge of retail investment in hedge funds as being of concern to the RBA.

Buffini's article is headed "RBA Warns on Hedge Funds", but in fact the Jacobs & Black article identifies some real positives for the industry in Australia. Most importantly, the Australian regulatory regime makes no distinction between hedge funds and other managed funds; the same registration, operational and disclosure requirements apply to a fund regardless of whether it is a hedge fund or not. This is a great positive for the hedge funds industry and the financial services industry generally. There is no logic whatsoever in seeking to make special rules for hedge funds given the lack of clarity in what actually defines such a fund and the importance of all investments being treated on a comparable basis so investors can make proper assessments of risk and return. One of the reasons for the public concern about hedge funds in the US is that hedge funds aren't required to be registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission and that as a result transparency is limited.

Also highlighted in the Jacobs & Black article was the growing importance of the hedge fund industry as an exporter of financial services, even though Australian managers have generally not been adopted by Australian institutional investors (see also Australia as a Centre for Hedge Funds?)

Finally, the article notes the powerful diversifying features of hedge funds that are the result of their lack of correlation with sharemarkets and other traditional asset classes eg over the past five years the Australian hedge fund industry has delivered a return in line with local sharemarkets - 12% - but with half the standard deviation, a generally accepted measure of risk. For Australian investors with high weights to Australian shares and property that have performed well in the last several years, investing in assets that are not correlated with Australian shares and property is likely to be VERY important for portfolio diversification.

Jacobs & Black offer hints of concerns about fees and about transparency, but both factors face considerable commercial pressure, particularly among institutional investors. The article also raises the spectre of leverage that is generally adopted by hedge funds (and private equity) and the potential systemic risk this brings to bear on the Australian financial system. This is a matter that does fall directly at the doorstep of the Bank and requires monitoring. However, current investments in hedge funds are currently very low in the total of Australian savings, and though these funds employ leverage, this is not yet a matter that should be of concern.

It would be helpful for policy makers and market participants to have better data on the amount of leverage employed by hedge funds. There are a number of data providers who are developing better information on Australian funds. The LCA Group which was referenced in the Jacobs & Black article have a quarterly publication with news stories and performance tables and Investment & Technology is working on performance reporting. Aggregate leverage and exposure data, as well as other directory information, is expected to be provided by a new industry survey to be published shortly. Leverage information on overseas funds invested in by Australians may be more difficult to determine, particularly given the limited information made available by fund of funds and the weaker requirements for transparency in other jurisdictions.

One important matter omitted from the Jacob & Black article was reference to the amount of retail hedge funds that carry capital guarantees where the risk of capital loss has been limited. In Australia, a large share of Australian retail investor hedge funds offer investments guaranteed at maturity. In these cases, the floor on returns makes them less risky than many naked sharemarket funds and property.

The Jacobs & Black article notes that the proportion of investments by retail investors in Australia is higher than in the US. This is partly the result of the slower uptake by institutional investors in Australia and partly that US hedge fund managers are limited by regulation to offering their products to accredited investors, such as those that have net worth in excess of US$1 million. In an environment where hedge fund managers were licensed, as they are in Australia, and investors are provided with suitable information about the fund and the manager responsible, then naturally one would expect a higher take-up by retail investors. The proportion of investors participating in hedge funds could be reduced in Australia by simply prohibiting such investments and limiting choice, but this is unlikely to be beneficial from a portfolio risk management perspective. In view of the volatility (risk) data provided by the authors removing an asset class with low correlation to traditional asset classes would likely raise the exposure of retail investors to the inevitable correction in share and property markets.

The comment that hedge funds are difficult to assess because they depend on manager skill is a glib one. Broad asset class returns are also difficult to predict, and as noted above, can exhibit far greater volatility (risk) than hedge funds. Buffini quotes financial adviser Rick Capel of Capel & Associates who noted that hedge funds have not been tested in a wholesale market meltdown (decline). The question for investors of course is whether they would be better served by being exposed to sharemarkets or hedge funds in a market meltdown. As Jacobs & Black pointed out, more than half of Australia's hedge funds (and this would be indicative globally) are long/short equity funds including market neutral; these are just the funds that would be expected to perform best in such an environment.

Nevertheless, a market meltdown would impact those hedge funds that carry a long bias to sharemarkets. Just as market returns have contributed to the return of such funds a market decline, unless the fund was particularly nimble, would detract from hedge fund returns and may even contribute to losses. Again, survey data on aggegrate fund market exposure and leverage would help determine whether there was significant market risk in hedge fund portfolios.

In fact it could be argued that the real risk for retail investors is not the complexity and risks associated with hedge funds, but the more traditional risk of constructing investment portfolios based on recent historical returns. Presently, Australian retail investors risk being seduced into raising and even leveraging Australian share exposure, following a period of strong returns over the past three years, and not taking the opportunity to introduce risk-reducing investments such as hedge funds.

With hedge funds, like any investment, investors need to diversify their approach. This appears to have been the case with high profile Amaranth (See Amaranth Losses - Lessons for Australia). Although the fund did lose substantial sums of investors' money, individual investors appear to have been well diversified and generally had other investments against which this loss could be matched.

In summary, the Jacobs & Black article is a good account of the current state of the Australian hedge fund industry. It highlights some important postives for this young and growing industry. Care should be taken not to tar the Australian hedge fund industry with the same brush as overseas funds where there have been a number of high profile collapses and concerns about transparency that can in part be attributed to the unregulated nature of hedge funds. In contrast, Australian hedge funds have the benefit of a regulator that requires the same degree of operational and disclosure requirements as other funds offered to Australian investors. And impending new data on the Australian hedge fund industry should help defray concerns that are simply not warranted at this stage of the industry's development.

Sunday, November 19, 2006

Monday, September 25, 2006

Amaranth Losses - Lessons for Australia?

In an earlier post on this site, I highlighted Reserve Bank of Australia Governor Glen Steven's concerns about hedge fund failure and the adverse impact such failure may have on Australia's financial system. In the same week that Mr Stevens delivered his speech in Hong Hong, prominent US hedge fund manager Amaranth Advisors was facing a major setback in its US$9. 2billion fund, losing US$6 billion on a natural gas investment strategy.

Amaranth manage a multi-strategy fund that delivered strong returns over recent years. There website described their approach as following a "broad spectrum of alternative investment and trading strategies in a highly disciplined, risk-controlled manner." However, according to the New York Times on 23 Sep 2006, a significant part of recent returns had been driven by trading-related profits from energy and commodities; contributions of US$1.26 billion in 2005 and US$2.17 billion Jan to Aug 2006. There was clue to the risk adopted in the fund with a 10% decline in May offset by high returns in April and June.

Apparently, the Fund held a position that would benefit if the spread between the March and April 2007 natural gas contracts rose. In the event they declined, and presumably because the positions were leveraged, the fund then had to meet substantial margin calls and/or close the positions in loss. In the end, the energy book was closed on 20 Sep and the fund realised a US$6 billion loss and a decline of 65% for the month and 55% calendar year to date.

One of the factors contributing to this outcome was liquidity in this commodity market. This was one of the risks raised by Mr Stevens. He said that just when liquidity is needed most, at a point of crisis, it is not available. This might spell trouble for the hedge fund, but what concerned Mr Stevens was the risk of destabilising the financial sysytem as a whole, as was the case with the failure of Long-Term Capital Management in 1998. Surprinsgly, given the size of the losses recorded at Amaranth there has been little flow-on impact observed so far. Its early days in this apparent failure, but this is encouraging.

Are there any lessons for Australia? The surprise is that this occurred in a so-called multi-strategy fund where an investor might expect a diversified set of strategies to drive returns. The fund had disclosed that energy had contributed 78% of year to June results of 20%+, suggesting limited diversification. The size of these gains and the subsequent losses are presumably the result of leverage. If the natural gas strategy was within the mandate for the Fund, and rational investors were aware of this mandate, they could have acted to ensure their own portfolios were suitably diversified and could cope with failure in any one position.

A knee-jerk response would be say that investing in hedge funds is risky and should be limited or prohibited. A more considered response would be to ensure that investment strategies/mandates, including leverage, are clearly set out in ASIC-registered Product Disclosure Statements. Armed with this information indivual investors and their advisers would then be in a position to make appropriate portfolio structuring decisions, that will protect investors from invidual investment failure.

Amaranth manage a multi-strategy fund that delivered strong returns over recent years. There website described their approach as following a "broad spectrum of alternative investment and trading strategies in a highly disciplined, risk-controlled manner." However, according to the New York Times on 23 Sep 2006, a significant part of recent returns had been driven by trading-related profits from energy and commodities; contributions of US$1.26 billion in 2005 and US$2.17 billion Jan to Aug 2006. There was clue to the risk adopted in the fund with a 10% decline in May offset by high returns in April and June.

Apparently, the Fund held a position that would benefit if the spread between the March and April 2007 natural gas contracts rose. In the event they declined, and presumably because the positions were leveraged, the fund then had to meet substantial margin calls and/or close the positions in loss. In the end, the energy book was closed on 20 Sep and the fund realised a US$6 billion loss and a decline of 65% for the month and 55% calendar year to date.

One of the factors contributing to this outcome was liquidity in this commodity market. This was one of the risks raised by Mr Stevens. He said that just when liquidity is needed most, at a point of crisis, it is not available. This might spell trouble for the hedge fund, but what concerned Mr Stevens was the risk of destabilising the financial sysytem as a whole, as was the case with the failure of Long-Term Capital Management in 1998. Surprinsgly, given the size of the losses recorded at Amaranth there has been little flow-on impact observed so far. Its early days in this apparent failure, but this is encouraging.

Are there any lessons for Australia? The surprise is that this occurred in a so-called multi-strategy fund where an investor might expect a diversified set of strategies to drive returns. The fund had disclosed that energy had contributed 78% of year to June results of 20%+, suggesting limited diversification. The size of these gains and the subsequent losses are presumably the result of leverage. If the natural gas strategy was within the mandate for the Fund, and rational investors were aware of this mandate, they could have acted to ensure their own portfolios were suitably diversified and could cope with failure in any one position.

A knee-jerk response would be say that investing in hedge funds is risky and should be limited or prohibited. A more considered response would be to ensure that investment strategies/mandates, including leverage, are clearly set out in ASIC-registered Product Disclosure Statements. Armed with this information indivual investors and their advisers would then be in a position to make appropriate portfolio structuring decisions, that will protect investors from invidual investment failure.

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

Reserve Bank of Australia's Stevens Flags Australian Hedge Fund Risk

Pointedly for the fledgling Australian hedge fund industry, incoming Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, Glen Stevens has issued a strong warning that hedge funds pose a risk to financial stability which is difficult for regulators to deal with. Mr Stevens was speaking at an event organised by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority and the Hong Kong Association of Banks on 15 September 2006.

According to the ABC, Mr Stevens said that the increased use of debt and the growing complexity of investments could disrupt markets when harder times came, as they surely would. He said it would be under abnormal conditions, when liquidity in markets was under pressure, that difficulties could arise. This post reviews Mr Steven's speech and seeks to identify areas that participants in the hedge fund industry in Australia should be aware of.

In particular, Mr Stevens referred to hedge funds as being "lightly regulated and often highly leveraged." While this might be the case globally, it is less true in Australia where investment managers are licensed under ASIC supervision and disclosure for retail funds at least is required by ASIC to be included in Product Disclosure Statements (PDSs). Admitedly an absence of industry wide data makes it hard to assess, but anecdotely hedge fund products in Australia are generally not highly leveraged.

Hedge funds' record of rapid growth and high reported returns has attracted a lot of attention by investors, Mr Stevens said. Ten years ago hedge funds were regarded as an exotic asset class, but now they are increasingly seen as part of the main stream for pension funds, university endowments and the like. Financial institutions are also increasingly in the habit of establishing in-house vehicles to tap the appetite for hedge-fund-type investments on the part of investors. Mr Stevens is right that awareness of hedge funds has increased dramatically in Australia in recent years, and while holdings of such funds have increased, they still represent a small weight in institutional and retail portfolios. In another post on this blog on 17 August 2006 titled Australian Superannuation Funds Use of Hedge Funds, a survey by the University of NSW and the Australian chapter of AIMA showed that current allocation to hedge funds by Australian superannuation funds of under 3% is expected to rise to over 4% over the next 2-5 years. Similar data for retail has not been compiled, but is likely to be similar.

According to Mr Stevens, the very term 'hedge fund' seems to be used rather more loosley than it used to be: he says we are really talking about any investment vehicle which is willing and able to take advantage of the vast array of financial products, 24-hour trading and ample liquidity to expose the funds of sophsticated investors to virtually any conceivable type of risk. The range of risks and lack of correlation with traditional equity and bond asset classes of course is one of the real attractions of hedge funds.

In Australia, hedge funds are not necessarily lightly regulated; they are treated by the regulator in much the same way as other managed investment vehicles. Around half of Australian hedge funds are retail managed funds that are carried in a PDS and registered with ASIC. Many of the wholesale and overseas investor funds/mandates have strategies that mirror the Australian retail offerings and Australian-based managers operate with an Australian Financial Services Licence.

Mr Stevens observed that by exploiting (and thereby eliminating) pricing anomalies and by being less encumbered by prudential controls than most other financial institutions, hedge funds promote efficiency in the allocation of capital by searching out returns more effectively than others. On the assumption, moreover, that those who put money into hedge funds know what risks they are taking - which might, increasingly, be a big assumption - people might take the view that what investors do with their money is their own business. Rather than being less encumbered by prudential controls imposed by the law, hedge funds are less encumbered by the mandate they have been given by investors and their advisers. The well-intentioned limits that have grown up around more traditionally managed monies have come at cost in terms of flexibility and ultimately return. The shift to hedge funds is a practical acknowledgement that straight-jacketing an investment manager will curb investment returns, and may even increase risk if the limits include limits on the use of hedging.

Critics, on the other hand says Stevens, claim that hedge funds can overwhelm and distort small markets; a tendency for herd behaviour, and application of leverage, amplifies the problem. When hedge funds decide simulataneously to get into or out of a position, they can disrupt market functioning. The entities in question are essentially those financial investment vehicles which are outside the normal pridential regulatory net. The situation that Mr Stevens describes threatens market integrity and is something that the RBA should be very sensitive to and monitor closely. However, it would be useful to know just how many entities are outside the "prudential net" as Mr Stevens put it. Is this a risk presented more by overseas funds that might be larger, better coordinated and more lightly regulated? The failed attempt by the SEC to require hedge fund registration may have been a setback in this respect. Ideally, a system that required registration in each major jurisdiction that was recognised in other jurisdictions with comparable regulation would be most effective.

In Australia, the rapid growth of AIMA's membership suggests a willingness of managers to understand the particular requirements of the Australian jurisdiction as AIMA has a strong regulatory and compliance element, including membership by leading legal and accounting firms in the hedge funds industry.

Mr Stevens highlighted two issues that regulators need to address:

Mr Stevens is sceptical of the argument that hedge funds necessarily add to liquidity. Under conditions of pressure, Mr Stevens argues that leveraged investors are more likely to need to use the liquidity of the market than to be able to contribute to it. On such occasions - which is when liquidity is needed most - these funds surely are liquidity takers, not providers he says. This argument, however, doesn't acknowledge one of the real benefits that hedge funds bring to markets - the use of short selling - which provides a natural offset to leveraged investments. This allows both buyers and sellers to express their view no matter what their current holding in a security.

Mr Stevens also suggests that hedge funds might command undue market power because of the brokerage they generate for investment banks. It is brave to suggest that listed markets can be manipulated in this way without risk of loss. In any case, such opportunities would be limited to particular hedge fund strategies and asssumes that for a particular transaction, market forces can somehow be subverted by these financial institutions in favour of hedge funds. This is a risk, but frankly in a properly functioning market unlikely to occur.

In summary, much of the risks that have been put forward by Mr Stevens could be asssessed by simply taking a closer look at the participants in Australia and the strategies they are adopting. In view of the fact that Mr Stevens is the incoming Governor of the RBA his comments deserve to be addressed. As half of the hedge funds in Australia are retail managed funds, their strategies are outlined in PDSs which are registered with ASIC. Public information could be supplemented by surveys that determine how many strategies involve leverage and what amount of everage is used.

According to the ABC, Mr Stevens said that the increased use of debt and the growing complexity of investments could disrupt markets when harder times came, as they surely would. He said it would be under abnormal conditions, when liquidity in markets was under pressure, that difficulties could arise. This post reviews Mr Steven's speech and seeks to identify areas that participants in the hedge fund industry in Australia should be aware of.

In particular, Mr Stevens referred to hedge funds as being "lightly regulated and often highly leveraged." While this might be the case globally, it is less true in Australia where investment managers are licensed under ASIC supervision and disclosure for retail funds at least is required by ASIC to be included in Product Disclosure Statements (PDSs). Admitedly an absence of industry wide data makes it hard to assess, but anecdotely hedge fund products in Australia are generally not highly leveraged.

Hedge funds' record of rapid growth and high reported returns has attracted a lot of attention by investors, Mr Stevens said. Ten years ago hedge funds were regarded as an exotic asset class, but now they are increasingly seen as part of the main stream for pension funds, university endowments and the like. Financial institutions are also increasingly in the habit of establishing in-house vehicles to tap the appetite for hedge-fund-type investments on the part of investors. Mr Stevens is right that awareness of hedge funds has increased dramatically in Australia in recent years, and while holdings of such funds have increased, they still represent a small weight in institutional and retail portfolios. In another post on this blog on 17 August 2006 titled Australian Superannuation Funds Use of Hedge Funds, a survey by the University of NSW and the Australian chapter of AIMA showed that current allocation to hedge funds by Australian superannuation funds of under 3% is expected to rise to over 4% over the next 2-5 years. Similar data for retail has not been compiled, but is likely to be similar.

According to Mr Stevens, the very term 'hedge fund' seems to be used rather more loosley than it used to be: he says we are really talking about any investment vehicle which is willing and able to take advantage of the vast array of financial products, 24-hour trading and ample liquidity to expose the funds of sophsticated investors to virtually any conceivable type of risk. The range of risks and lack of correlation with traditional equity and bond asset classes of course is one of the real attractions of hedge funds.

In Australia, hedge funds are not necessarily lightly regulated; they are treated by the regulator in much the same way as other managed investment vehicles. Around half of Australian hedge funds are retail managed funds that are carried in a PDS and registered with ASIC. Many of the wholesale and overseas investor funds/mandates have strategies that mirror the Australian retail offerings and Australian-based managers operate with an Australian Financial Services Licence.

Mr Stevens observed that by exploiting (and thereby eliminating) pricing anomalies and by being less encumbered by prudential controls than most other financial institutions, hedge funds promote efficiency in the allocation of capital by searching out returns more effectively than others. On the assumption, moreover, that those who put money into hedge funds know what risks they are taking - which might, increasingly, be a big assumption - people might take the view that what investors do with their money is their own business. Rather than being less encumbered by prudential controls imposed by the law, hedge funds are less encumbered by the mandate they have been given by investors and their advisers. The well-intentioned limits that have grown up around more traditionally managed monies have come at cost in terms of flexibility and ultimately return. The shift to hedge funds is a practical acknowledgement that straight-jacketing an investment manager will curb investment returns, and may even increase risk if the limits include limits on the use of hedging.

Critics, on the other hand says Stevens, claim that hedge funds can overwhelm and distort small markets; a tendency for herd behaviour, and application of leverage, amplifies the problem. When hedge funds decide simulataneously to get into or out of a position, they can disrupt market functioning. The entities in question are essentially those financial investment vehicles which are outside the normal pridential regulatory net. The situation that Mr Stevens describes threatens market integrity and is something that the RBA should be very sensitive to and monitor closely. However, it would be useful to know just how many entities are outside the "prudential net" as Mr Stevens put it. Is this a risk presented more by overseas funds that might be larger, better coordinated and more lightly regulated? The failed attempt by the SEC to require hedge fund registration may have been a setback in this respect. Ideally, a system that required registration in each major jurisdiction that was recognised in other jurisdictions with comparable regulation would be most effective.

In Australia, the rapid growth of AIMA's membership suggests a willingness of managers to understand the particular requirements of the Australian jurisdiction as AIMA has a strong regulatory and compliance element, including membership by leading legal and accounting firms in the hedge funds industry.

Mr Stevens highlighted two issues that regulators need to address:

- Ensuring there is sufficient disclosure to allow investors to make informed judgements about the risks and returns. In Australia, the regulatory authorities draw no distinction between hedge funds and other investment managers; the regulatory regime is determined by what the entity does, rather than what it is called. This ensures a level playing field.

- Ensuring that the activities of investment managers which are not subject to prudential supervision do not threaten the financial viability of firms, such as banks, that are. This approach emphasises to the counterparties of hedge funds and other highly leveraged institutions (such as prime brokers, banks and investment houses) the importance of strong risk management, collateral, knowing their customer and so on. The aim here is to preserve the prudential strength of the core part of the sysstem in the interests of economic financial stability, while allowing the part beyond the prudential net to play its role in taking on risk.

Mr Stevens is sceptical of the argument that hedge funds necessarily add to liquidity. Under conditions of pressure, Mr Stevens argues that leveraged investors are more likely to need to use the liquidity of the market than to be able to contribute to it. On such occasions - which is when liquidity is needed most - these funds surely are liquidity takers, not providers he says. This argument, however, doesn't acknowledge one of the real benefits that hedge funds bring to markets - the use of short selling - which provides a natural offset to leveraged investments. This allows both buyers and sellers to express their view no matter what their current holding in a security.

Mr Stevens also suggests that hedge funds might command undue market power because of the brokerage they generate for investment banks. It is brave to suggest that listed markets can be manipulated in this way without risk of loss. In any case, such opportunities would be limited to particular hedge fund strategies and asssumes that for a particular transaction, market forces can somehow be subverted by these financial institutions in favour of hedge funds. This is a risk, but frankly in a properly functioning market unlikely to occur.

In summary, much of the risks that have been put forward by Mr Stevens could be asssessed by simply taking a closer look at the participants in Australia and the strategies they are adopting. In view of the fact that Mr Stevens is the incoming Governor of the RBA his comments deserve to be addressed. As half of the hedge funds in Australia are retail managed funds, their strategies are outlined in PDSs which are registered with ASIC. Public information could be supplemented by surveys that determine how many strategies involve leverage and what amount of everage is used.

Tuesday, September 05, 2006

Listing Hedge Funds

There is a vibrant Listed Investment Company community on the Australian Stock Exchange that includes companies managing Australian equities, overseas equities and other specialist funds. Is there a value in listing hedge funds as an alternative to offering hedge funds as retail managed funds?

In other markets, such as Ireland and Singapore, listing is offered as an alternative "structure of convenience" to allow investors to participate that might otherwise be constrained by an unlisted vehicle or the jurisdiction of the particular fund company, particualrly if it is located in a non-tax treaty country such as the Cayman Islands.

What happens in practice in these situations is little different from the unlisted model. Applications and redemptions occur at the posted price for the day rather than a market price struck by the meeting of buyers and sellers as is generally the case in listed markets. As a result, there are net applications and redemptions on a day that are managed by the fund administrator. Prices are published by the exchange, but little additional investor comfort is gained from the listing.

It is possible to list a Cayman fund for example on the Irish Stock Exchange (ISE). This can be done with little additional documentation than required to establish the fund registered with the Cayman Monetary Authority. If the fund has already commenced, trading an Audited Statement of Net Assets will be required at the time of listing, otherwsie no accompanying financials are required. Once the fund is listed, the day-to-day operation of the fund is usually the responsibility of the Administrator. This will include the calculation of the net asset value and processing the subscription and redemption applications.

Because it is not possible to subscribe or redeem shares at any other price other than the net asset value, there is no opportunity for investors to exploit pricing differences ie there is no secondary market for investment funds on the ISE, so a listed fund on the ISE is not actively traded.

The listing of an investment fund on such exchanges as the ISE or Singapore Stock Exchange are simply a "technical listings"; marketing tools to assist a fund access a wider investor base. For example, it is useful where a fund seeks to target institutional investors. A listing can facilitate distribution because some such investors are often prohibited from investing in unlisted securities.

In other markets, such as Ireland and Singapore, listing is offered as an alternative "structure of convenience" to allow investors to participate that might otherwise be constrained by an unlisted vehicle or the jurisdiction of the particular fund company, particualrly if it is located in a non-tax treaty country such as the Cayman Islands.

What happens in practice in these situations is little different from the unlisted model. Applications and redemptions occur at the posted price for the day rather than a market price struck by the meeting of buyers and sellers as is generally the case in listed markets. As a result, there are net applications and redemptions on a day that are managed by the fund administrator. Prices are published by the exchange, but little additional investor comfort is gained from the listing.

It is possible to list a Cayman fund for example on the Irish Stock Exchange (ISE). This can be done with little additional documentation than required to establish the fund registered with the Cayman Monetary Authority. If the fund has already commenced, trading an Audited Statement of Net Assets will be required at the time of listing, otherwsie no accompanying financials are required. Once the fund is listed, the day-to-day operation of the fund is usually the responsibility of the Administrator. This will include the calculation of the net asset value and processing the subscription and redemption applications.

Because it is not possible to subscribe or redeem shares at any other price other than the net asset value, there is no opportunity for investors to exploit pricing differences ie there is no secondary market for investment funds on the ISE, so a listed fund on the ISE is not actively traded.

The listing of an investment fund on such exchanges as the ISE or Singapore Stock Exchange are simply a "technical listings"; marketing tools to assist a fund access a wider investor base. For example, it is useful where a fund seeks to target institutional investors. A listing can facilitate distribution because some such investors are often prohibited from investing in unlisted securities.

Friday, August 25, 2006

Australia as a Centre for Hedge Funds?

Australia has a growing hedge fund industry, but the main hedge fund centres remain London and New York. While Australia has the largest amount of hedge funds under management in the region (recently estimated at $40 billion), a respected regulatory regime and high quality people, it is Hong Kong, Singapore and possibly Tokyo that are vying for hedge fund leadership in Asia.

What would it take to set Sydney on a path of hedge fund leadership in the region?

The key stumbling block is tax, in particular withholding tax. While other jurisdictions have strong records in providing hedge fund services the main advantage they carry over Australia is tax. A number of centres, such as the Cayman Islands, Bermuda and British Virgin Islands have established a strong position in servicing hedge funds by offering a tax-free environment for investors and managers. Other developed markets such as the UK, Ireland, Luxembourg, Hong Kong, and Singapore do not impose withholding tax and market this as a key selling point in attracting foreign direct investment.

So what is the logic of withholding tax? Withholding taxes such as PAYE in Australia are designed to limit avoidance and evasion by taxing at the source of income. Withholding tax on non-residents however does not carry the same logic, except to reduce the opportunity for residents to configure their arrangements to appear to be non-residents and avoid domestic taxation. Applying withholding tax on non-residents is a case of cutting off our nose to spite our face; it may be effective in reducing avoidance activities of residents, but it is also effective in turning away genuine non-residents and spurning the development of an Australian hedge fund industry.

Withholding tax has the effect of securing taxation revenue from a small domestic hedge fund industry, but prospective taxation revenue on a new regional or global industry is foregone. Let me explain.

Currently, overseas investors in Australian hedge funds (and investments generally) are subject to withholding tax. While withholding tax is also applied in many countries that might compete with Australia for investors, there are other well-established jurisdictions that do not impose withholding tax and are thus in an advantaged position to offer hedge fund products.

Thus, to meet overseas demand for Australian hedge funds, Australian managers generally develop and offer hedge fund products by way of an offshore-based fund company registered in such jurisdictions as the Cayman Islands. Generally, investment management is conducted by an Australian investment manager team either directly or by way of an advisory agreement with the fund company, although in some cases fund managers are incentivised to set up their entire businesses overseas. In any case, the related services of custody, prime broking, administration, legal, accounting and audit are generally delivered by overseas-appointed providers.

For offshore structured Australian hedge funds, the Australian government does participate in the taxation revenue associated with a fund's earnings remitted to Australian participants. However, there is a substantial leakage of revenue from the absence of withholding tax (because the funds are not located in Australia) and both individual and corporate taxation proceeds from Australian service providers that are NOT being used by the overseas fund company. The Australian government will earn withholding tax on those investors who do choose to invest in Australian products despite the disadvantages of doing so. Withholding tax thus has the unintended impact of shackling jobs growth and lowering potential taxation revenue.

To be a centre for hedge funds, Australia needs to attract all the ancillary hedge fund service providers and to provide an environment that would encourage both Australian and overseas fund managers to set up in Australia rather the current situation of encouraging Australian fund managers to set up overseas. Hedge fund managers are not constrained to investing in domestic assets and so the domicile of a hedge fund business will be driven by factors such as tax, people and regulator.

The BOLD decision would thus be to remove withholding tax on all non-resident financial asset investments in Australia based on the expectation that the withholding tax forgone will be more than outweighed by higher corporate and individual taxation associated with increased exports of financial services and greater jobs growth and of course the collection cost of the withholding tax. Modelling this analysis would be a very worthy exercise.

The application of withholding tax is particularly inappropriate in the case of funds offered to overseas investors that invest primarily in overseas assets in what the authorities term "non-Australian things".

Thus, a SECOND BEST solution is to acknowledge that the current policy to tax Australian-sourced income regardless of residence of the investor will not change. In this event, we should accept that Australia will NEVER be a regional funds management centre and instead look to particular areas where Australia can grow the hedge fund industry on the margin to the mutual benefit of government and industry.

Australian fund managers investing in “Australian things” will continue to require an offshore structured fund company for overseas investors, and if warranted by demand from Australian investors a second fund with Australian service providers as Australian investors are limited by FIF in their investments in offshore fund companies. While this twin structure is costly and inefficient, it is the only practical way to proceed in these circumstances.

However, where a fund’s investors are exclusively non-resident and activities are principally related to “non-Australian things” these non-residents investors should be exempt from a withholding tax to allow Australian fund managers to compete globally.

For clarity, the fund should not be denominated in Australian dollars, Australian FIF rules should not apply, foreign exchange contracts would be permissible provided they were in respect of overseas assets and management fees would be taxable at the company tax rate.

To tackle the additional risk of avoidance by residents, the exemption could be set to only apply to those non-residents of tax treaty countries including on a “look through” to the ultimate holder of a trust.

Australian non-resident withholding tax is a material impediment to potential growth of the hedge fund (and financial services) industry in Australia. In view of the other advantages Australia carries in financial services, exempting non-residents from withholding tax (with some reasonable caveats) would take Australia to a position of regional leadership in hedge funds.

What would it take to set Sydney on a path of hedge fund leadership in the region?

The key stumbling block is tax, in particular withholding tax. While other jurisdictions have strong records in providing hedge fund services the main advantage they carry over Australia is tax. A number of centres, such as the Cayman Islands, Bermuda and British Virgin Islands have established a strong position in servicing hedge funds by offering a tax-free environment for investors and managers. Other developed markets such as the UK, Ireland, Luxembourg, Hong Kong, and Singapore do not impose withholding tax and market this as a key selling point in attracting foreign direct investment.

So what is the logic of withholding tax? Withholding taxes such as PAYE in Australia are designed to limit avoidance and evasion by taxing at the source of income. Withholding tax on non-residents however does not carry the same logic, except to reduce the opportunity for residents to configure their arrangements to appear to be non-residents and avoid domestic taxation. Applying withholding tax on non-residents is a case of cutting off our nose to spite our face; it may be effective in reducing avoidance activities of residents, but it is also effective in turning away genuine non-residents and spurning the development of an Australian hedge fund industry.

Withholding tax has the effect of securing taxation revenue from a small domestic hedge fund industry, but prospective taxation revenue on a new regional or global industry is foregone. Let me explain.

Currently, overseas investors in Australian hedge funds (and investments generally) are subject to withholding tax. While withholding tax is also applied in many countries that might compete with Australia for investors, there are other well-established jurisdictions that do not impose withholding tax and are thus in an advantaged position to offer hedge fund products.

Thus, to meet overseas demand for Australian hedge funds, Australian managers generally develop and offer hedge fund products by way of an offshore-based fund company registered in such jurisdictions as the Cayman Islands. Generally, investment management is conducted by an Australian investment manager team either directly or by way of an advisory agreement with the fund company, although in some cases fund managers are incentivised to set up their entire businesses overseas. In any case, the related services of custody, prime broking, administration, legal, accounting and audit are generally delivered by overseas-appointed providers.

For offshore structured Australian hedge funds, the Australian government does participate in the taxation revenue associated with a fund's earnings remitted to Australian participants. However, there is a substantial leakage of revenue from the absence of withholding tax (because the funds are not located in Australia) and both individual and corporate taxation proceeds from Australian service providers that are NOT being used by the overseas fund company. The Australian government will earn withholding tax on those investors who do choose to invest in Australian products despite the disadvantages of doing so. Withholding tax thus has the unintended impact of shackling jobs growth and lowering potential taxation revenue.

To be a centre for hedge funds, Australia needs to attract all the ancillary hedge fund service providers and to provide an environment that would encourage both Australian and overseas fund managers to set up in Australia rather the current situation of encouraging Australian fund managers to set up overseas. Hedge fund managers are not constrained to investing in domestic assets and so the domicile of a hedge fund business will be driven by factors such as tax, people and regulator.

The BOLD decision would thus be to remove withholding tax on all non-resident financial asset investments in Australia based on the expectation that the withholding tax forgone will be more than outweighed by higher corporate and individual taxation associated with increased exports of financial services and greater jobs growth and of course the collection cost of the withholding tax. Modelling this analysis would be a very worthy exercise.

The application of withholding tax is particularly inappropriate in the case of funds offered to overseas investors that invest primarily in overseas assets in what the authorities term "non-Australian things".

Thus, a SECOND BEST solution is to acknowledge that the current policy to tax Australian-sourced income regardless of residence of the investor will not change. In this event, we should accept that Australia will NEVER be a regional funds management centre and instead look to particular areas where Australia can grow the hedge fund industry on the margin to the mutual benefit of government and industry.

Australian fund managers investing in “Australian things” will continue to require an offshore structured fund company for overseas investors, and if warranted by demand from Australian investors a second fund with Australian service providers as Australian investors are limited by FIF in their investments in offshore fund companies. While this twin structure is costly and inefficient, it is the only practical way to proceed in these circumstances.

However, where a fund’s investors are exclusively non-resident and activities are principally related to “non-Australian things” these non-residents investors should be exempt from a withholding tax to allow Australian fund managers to compete globally.

For clarity, the fund should not be denominated in Australian dollars, Australian FIF rules should not apply, foreign exchange contracts would be permissible provided they were in respect of overseas assets and management fees would be taxable at the company tax rate.

To tackle the additional risk of avoidance by residents, the exemption could be set to only apply to those non-residents of tax treaty countries including on a “look through” to the ultimate holder of a trust.

Australian non-resident withholding tax is a material impediment to potential growth of the hedge fund (and financial services) industry in Australia. In view of the other advantages Australia carries in financial services, exempting non-residents from withholding tax (with some reasonable caveats) would take Australia to a position of regional leadership in hedge funds.

Friday, August 18, 2006

Participants in the Australian Hedge Fund Industry

The Australian hedge fund industry is young, but growing quickly. There are a number of hedge fund managers delivering single and multi-strategy products as well as aggregators offering fund of fund products. However, the available information on the make-up of the participants is sketchy.

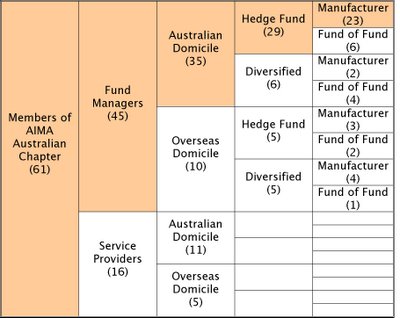

The Australian hedge fund industry is young, but growing quickly. There are a number of hedge fund managers delivering single and multi-strategy products as well as aggregators offering fund of fund products. However, the available information on the make-up of the participants is sketchy.The attached table examines the membership of the Australian Chapter of AIMA and dissects members according to some key criteria.

There are in excess of 1,000 members of AIMA globally and 61 (6%) members in the Australian Chapter. This is higher than Australia's weight in global sharemarkets for example. While there will be hedge fund managers who are not members of

AIMA, using this membership as a proxy for the industry as a whole in Australia shows some interesting results.

The first split shown is between fund managers (74%) and service providers (26%) such as lawyers, custodians, brokers and exchanges. Of the fund managers, 78% had their primary domicile in Australia and the balance overseas. Among the Australian domiciled managers, 83% were special purpose hedge fund managers and the others part of a diversified financial services business. Finally, 80% of hedge fund managers manufactured funds while the balance aggregated fund of funds.

In summary, of the 61 members of the AIMA's Australian Chapter, 23 (38%) are hedge fund manufacturers. These managers provide product for Australian retail and institutional investors, and in some cases overseas investors by way of special purpose vehicles or mandates.

Thursday, August 17, 2006

Australian Superannuation Funds Use of Hedge Funds

The assets of Australian Super funds total around $1 trillion and, despite the value of hedge funds in portfolio construction, have less than 3% invested in this asset class.

The University of NSW and the Australian chapter of AIMA conducted a survey in Jan 2006 aimed at examining the attitude of Super funds to hedge fund investing. The respondents to the survey carried funds under management of more than A$145 billion.

The key findings of the study were:

The University of NSW and the Australian chapter of AIMA conducted a survey in Jan 2006 aimed at examining the attitude of Super funds to hedge fund investing. The respondents to the survey carried funds under management of more than A$145 billion.

The key findings of the study were:

- current allocation of under 3% is expected to rise to over 4% over the next 2-5 years

- the current focus on global strategies is expected to remain - surprisingly only 14% were Australian-based strategies

- funds of funds represented 49% of investments, although this is expected to decline in favour of individual funds and multi strategy funds in future

- the most popular strategy is long/short equity

- operational and governance issues were most important to those considering investment

Tuesday, August 15, 2006

Australia's ASIC Studies Hedge Funds

Australia's financial services regulator, ASIC, is researching hedge funds in Australia to better understand the potential risks to investors. The study, based on publically available information, will not be published and will be used for internal purposes only.

In Australia, hedge funds may be offered to retail investors under a registered Product Disclosure Statement. Around half the A$20 billion Australian hedge fund industry is made up of registered funds.

A key observation of the study is that the funds offered are more benign then ASIC had expected in a number of respects; gearing, fees and profitability.

Also, there does not appear to be any disruptive influence by foreign-operated hedge funds on the efficient and proper functionaing of Australian markets.

As with all funds offered to Australian investors, ASIC is concerned that product documentation needs to be "clear, concise and effective". Hedge funds are not likely to be singled out in particular compared with other retail/mutual funds.

In Australia, hedge funds may be offered to retail investors under a registered Product Disclosure Statement. Around half the A$20 billion Australian hedge fund industry is made up of registered funds.

A key observation of the study is that the funds offered are more benign then ASIC had expected in a number of respects; gearing, fees and profitability.

Also, there does not appear to be any disruptive influence by foreign-operated hedge funds on the efficient and proper functionaing of Australian markets.

As with all funds offered to Australian investors, ASIC is concerned that product documentation needs to be "clear, concise and effective". Hedge funds are not likely to be singled out in particular compared with other retail/mutual funds.

Monday, August 14, 2006

What is a hedge fund?

The two defining features of a hedge fund are leverage and short selling. While traditional funds managers may also leverage and short sell they are generally conducted more extensively by hedge funds. There are other differences like fees, transparency of process and regulation which I will address in later posts.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)